New research helps us understand why some people are more likely to hold on to negative emotions than positive ones, which can happen with anxiety, depression, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and how to turn those negative emotions into positive ones.

Good or unpleasant memories are linked to a specific brain molecule, according to Salk Institute researchers and colleagues.

Their finding, which was published in Nature on July 20, 2022, helps us understand why some people are more likely to hold on to negative emotions than positive ones, which can happen with anxiety, depression, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Senior author Kay Tye says, “We’ve basically gotten a handle on the fundamental biological process of how you can remember if something is good or bad.”

“This is something that’s core to our experience of life,” the author adds, “and the notion that it can boil down to a single molecule is incredibly exciting.”

To learn whether to avoid or seek out a certain event in the future, a human or animal’s brain must link a good or negative emotion, or “valence,” with that stimulus. The process through which the brain is able to associate these feelings with a specific memory is referred to as “valence assignment.”

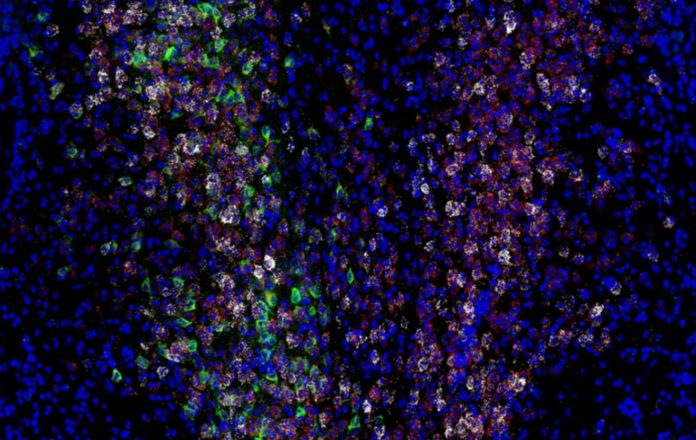

In 2016, Tye found that a cluster of neurons in the basolateral amygdala (BLA) of the brain aids in the valence assignment process in mice.

As the mice came to identify a tone with a sweet taste, one group of BLA neurons were engaged with positive valence.

As the rats came to identify a distinct tone with a bitter taste, a different set of BLA neurons were engaged with negative valence.

“We found these two pathways—analogous to railroad tracks—that were leading to positive and negative valence, but we still didn’t know what signal was acting as the switch operator to direct which track should be used at any given time,” explains Tye, holder of the Wylie Vale Chair.

The significance of the signaling chemical neurotensin to these BLA neurons was the focus of the new study.

They were already aware that a few additional neurotransmitters, such neurotensin, are produced by the cells connected to valence processing.

In order to selectively remove the neurotensin gene from the cells, they used CRISPR gene editing techniques. This is the first time that CRISPR has been used to isolate a particular neurotransmitter function.

Without neurotensin signaling in the BLA, mice were unable to assign positive valence and were unable to learn to correlate the initial tone with a positive stimulus.

Unexpectedly, negative valence was not blocked by neurotensin deficiency. Instead, the animals developed a stronger link between the second tone and a negative stimulus, becoming even more adept at negative valence.

According to the research, the neurons connected to negative valence are activated until neurotensin is released, which turns on the neurons connected to positive valence. This suggests that fear is the brain’s default state by design.

According to Tye, this makes sense from an evolutionary standpoint since it helps people stay away from potentially hazardous situations—and it presumably connects with people who tend to see the worst in a scenario.

Tye and her team’s subsequent research furthered the theory that neurotensin is the cause of positive valence by demonstrating that high levels of neurotensin improved reward learning and reduced negative valence.

According to co-first author and postdoctoral associate Hao Li of the Tye Lab, “We can actually manipulate this switch to turn on positive or negative learning. Ultimately, we’d like to try to identify novel therapeutic targets for this pathway.”

The researchers are still uncertain as to whether neurotensin levels in the human brain can be altered to treat anxiety or PTSD. Future research will also examine what other brain pathways and chemicals are involved in the release of neurotensin.

Image Credit: SALK INSTITUTE

You were reading: New Insight Could Help Us to Make Memories Less Traumatic