American researchers found traces of tissue renewal in the joints of the legs in humans. They measured the age of extracellular proteins in the articular cartilage and noticed that the farther the joint from the spine, the more young, newly formed proteins in it. In addition, in the renewing tissue, scientists found increased expression of microRNAs that are found in animals capable of regeneration – for example, axolotls.

Compared to fish and amphibians, most mammals have lost the ability to regenerate limbs. In humans, amputated fingertips can grow back, but only in early childhood. However, even damaged skeletal tissue does not regenerate in adults, for example, with osteoarthritis – at least, it was thought so far.

A group of scientists from Duke University School of Medicine, led by Virginia Kraus, decided to measure the age of individual molecules in the extracellular substance of cartilage. Outside cells, some amino acids in proteins are known to undergo random non-enzymatic hydrolysis. As a result, amides are converted to acids, and glutamate (glutamic acid) and aspartate are formed from glutamine and asparagine. By the ratio of aspartate to asparagine, one can estimate the lifetime of a particular protein site.

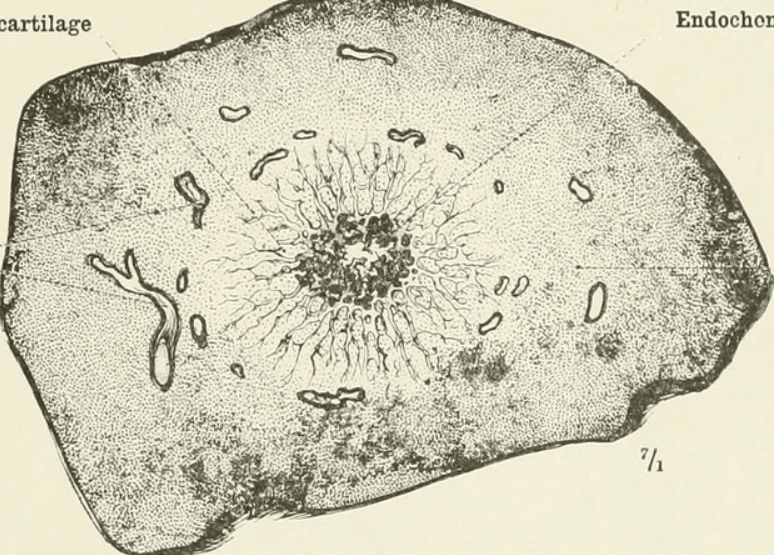

Researchers worked with samples of healthy and damaged cartilage tissue. They received healthy tissue after operations related to injuries, and the diseased tissue from patients with osteoarthritis; in total, they collected 18 different samples. Scientists measured the age of various extracellular proteins – collagen, aggrecan, fibronectin and others – and noticed that in the distal joints (ankle) the proteins are younger than in the proximal (femoral).

Scientists have suggested that different rates of extracellular protein recovery are a manifestation of the ability to regenerate, which is partially preserved in the distal extremities and disappears in the proximal. Then, with the destruction of the joint that accompanies osteoarthritis, the same regeneration processes should start in the cartilage.

To test their hypothesis, the researchers measured in cartilage tissue the expression of characteristic microRNAs that were previously found in other animals with high regeneration abilities – axolotl and zebrafish. In samples with osteoarthritis, the concentration of these miRNAs was two times higher than in healthy cartilage, and in the ankle – two to five times higher than in the shoulder, depending on the type of miRNA.

Thus, scientists have confirmed that under stress and tissue destruction in human cartilage, the same processes are launched as in the regenerating limbs of amphibians and fish fins. In the distal sections, they work more actively, and perhaps this explains the fact that osteoarthritis is less common in the ankle than in the femoral joint. Researchers do not exclude that the stimulation of precisely these regeneration processes – possibly injection of the corresponding miRNAs – will make it possible to better repair damaged articular cartilages in the future.

Scientists believe that osteoarthritis is a very ancient disease, and probably appeared in fish, along with the first real joints. However, the mechanisms of its occurrence have never been studied, and researchers have to, for example, specifically injure the knees of the sheep in order to follow its development.

Via | Journal Science