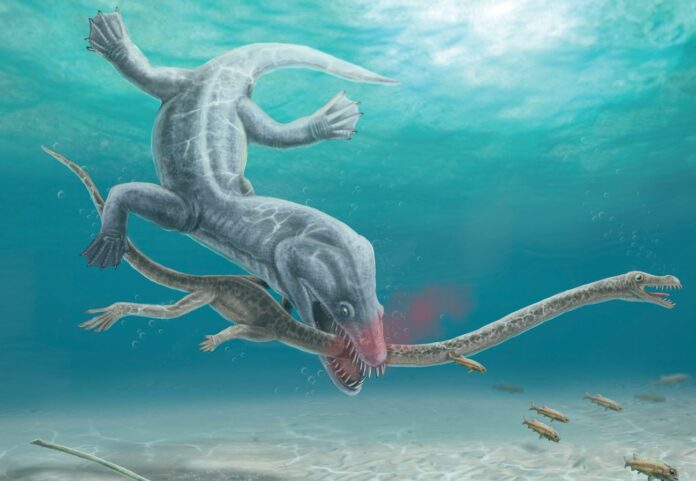

From the depths of the fossil record, an unsettling truth emerges, confirming that long-necked reptiles met their fate through decapitation by predators.

During the era of dinosaurs, marine reptiles exhibited significantly longer necks compared to present-day reptiles. Although this evolutionary strategy proved successful, scientists have long speculated that these elongated bodies made them vulnerable to predators. Now, after nearly two centuries of extensive research, conclusive fossil evidence validates this hypothesis in an extraordinarily vivid manner.

In a study published in the journal Current Biology today, researchers investigated the unique neck structures of two Tanystropheus species from the Triassic period. Tanystropheus is a reptile species distantly related to crocodiles, birds, and dinosaurs. These particular species possessed distinctive necks composed of 13 greatly elongated vertebrae, supported by sturdy rib-like structures. Consequently, these marine reptiles likely had rigid necks and adopted an ambush strategy to capture their prey. However, it appears that the predators of Tanystropheus also capitalized on their long necks to their advantage.

A thorough examination of fossilized bones from two distinct specimens, each representing a different species, has unveiled unmistakable bite marks on their necks, with one specimen even revealing a fracture at the precise location of the bite.

These findings present macabre and exceptionally uncommon evidence of predator-prey interactions in the fossil record, dating back over 240 million years, according to the researchers.

“Paleontologists speculated that these long necks formed an obvious weak spot for predation, as was already vividly depicted almost 200 years ago in a famous painting by Henry de la Beche from 1830,” explains Stephan Spiekman of the Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Stuttgart, Germany. “Nevertheless, there was no evidence of decapitation—or any other sort of attack targeting the neck—known from the abundant fossil record of long-necked marine reptiles until our present study on these two specimens of Tanystropheus.”

Spiekman’s PhD study at the Paleontological Museum of the University of Zurich in Switzerland, where the fossils are kept, focused mostly on these reptiles. He noticed that two types of Tanystropheus lived in the same area. One was small, about 1.5 meters long, and probably ate soft-shelled animals like shrimp. The other was much bigger, up to 6 meters long, and probably ate fish and squid. The shape of the head also showed that Tanystropheus probably spent most of its time in the water.

The well-preserved heads and necks of two specimens of this species were well-known to have abrupt ends. Although no one had conducted a thorough investigation, it had been assumed that their necks had been bit off. Spiekman collaborated on the new study with Eudald Mujal, a research associate at the Institut Català de Paleontologia in Spain and an expert in the preservation of fossils and predatory interactions in the fossil record based on bite marks on bones. Mujal is also from the Stuttgart Museum. They spent a day in Zurich scrutinizing the two specimens before coming to the conclusion that the necks had definitely been bit off.

“Something that caught our attention is that the skull and portion of the neck preserved are undisturbed, only showing some disarticulation due to the typical decay of a carcass in a quiet environment,” Mujal adds. “Only the neck and head are preserved; there is no evidence whatsoever of the rest of the animals. The necks end abruptly, indicating they were completely severed by another animal during a particularly violent event, as the presence of tooth traces evinces.”

“The fact that the head and neck are so undisturbed suggests that when they reached the place of their final burial, the bones were still covered by soft tissues like muscle and skin,” Mujal further adds. “They were clearly not fed on by the predator. Although this is speculative, it would make sense that the predators were less interested in the skinny neck and small head, and instead focused on the much meatier parts of the body. Taken together, these factors make it most likely that both individuals were decapitated during the hunt and not scavenged, although scavenging can never be fully excluded in fossils that are this old.”

“Interestingly, the same scenario—although certainly executed by different predators—played out for both specimens, which remember, represent individuals of two different Tanystropheus species, which are very different in size and possibly lifestyle,” Spiekman adds.

The research affirms previous conclusions made by scientists that the necks of ancient reptiles constituted a truly distinctive evolutionary adaptation, distinct from the broader and more flexible necks observed in long-necked plesiosaurs. The findings further indicate that the development of an elongated neck in marine reptiles carried certain drawbacks. However, the researchers emphasize that despite the potential disadvantages, the evolution of elongated necks undeniably represented an immensely successful and enduring strategy employed by numerous marine reptiles over a remarkable duration of 175 million years.

“In a very broad sense, our research once again shows that evolution is a game of trade-offs,” Spiekman adds. “The advantage of having a long neck clearly outweighed the risk of being targeted by a predator for a very long time. Even Tanystropheus itself was quite successful in evolutionary terms, living for at least 10 million years and occurring in what is now Europe, the Middle East, China, North America, and possibly South America.”

Image Credit: Roc Olivé (Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont)/FECYT