Experiencing a belly-flop into a pool teaches us that water can feel unexpectedly solid when approached from the wrong angle. Interestingly, numerous kingfisher species manage to dive headfirst into water seamlessly to capture their aquatic prey.

“There’s gotta be something they’re doing that protects them from the negative influences of repeatedly landing on their heads on the water’s surface.”

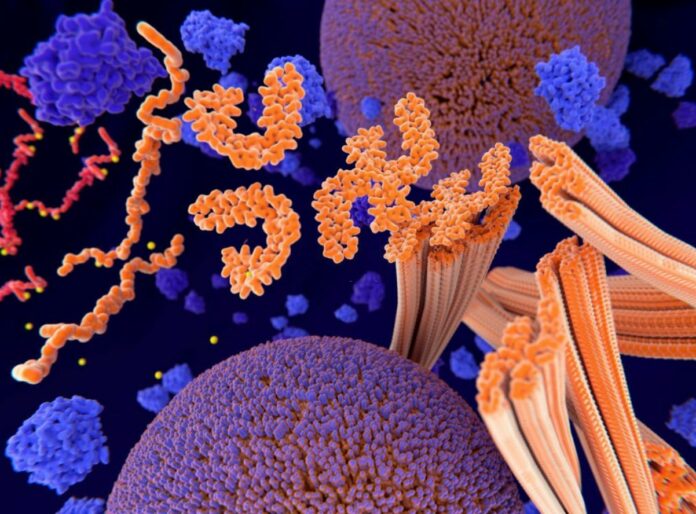

How Kingfishers Dive Headfirst Into The Water Without Hurting Their Brains?

Chad Eliason, a research scientist at the Field Museum in Chicago and lead author of the study, highlights, “It’s a high-speed dive from air to water, and it’s done by very few bird species.”

The recent scientific investigation published in Communications Biology delves into the genetic makeup of 30 different kingfisher species, aiming to unveil the genetic factors that enable these birds to dive effectively without causing harm to their brains.

Kingfishers engage in a unique form of diving, known as ‘plunge-diving,’ which is a high-velocity transition from air to water, observed in only a select few bird species.

Shannon Hackett, associate curator of birds at the Field Museum and senior author of the study, suggests that “For kingfishers to dive headfirst the way they do, they must have evolved other traits to keep them from hurting their brains.”

It is noteworthy that not all kingfishers feed on aquatic life; many species prey on terrestrial creatures like insects, lizards, and sometimes, other kingfishers.

Prior research led by Jenna McCollough and Michael Andersen from the University of New Mexico demonstrated through DNA analysis that kingfisher groups with fish-based diets are not closely related within the kingfisher family tree.

This finding implies that the ability to dive and the preference for a fish-based diet have evolved multiple times independently among kingfishers, rather than stemming from a single fish-eating ancestor.

Hackett finds the numerous independent evolutions of diving within the kingfisher species to be both intriguing and scientifically valuable, providing a robust platform to seek a comprehensive understanding of why this trait has evolved so frequently.

“If a trait evolves a multitude of different times independently, that means you have power to find an overarching explanation for why that is.”

In this research project, the team of investigators, comprising Lauren Mellenthin, now affiliated with Yale University but an undergraduate intern at Field Museum during the research period, Taylor Hains from the University of Chicago and Field Museum, Stacy Pirro from Iridian Genomes, and Michael Anderson and Jenna McCullough from the University of New Mexico, delved into the genetic material of 30 different kingfisher species, encompassing both piscivorous and non-piscivorous varieties.

Eliason, affiliated with the Field’s Grainger Bioinformatics Center and Negaunee Integrative Research Center, explained that they utilized bird specimens from the Field Museum’s collections to extract the kingfisher DNA.

“To get all the kingfisher DNA, we used specimens in the Field Museum’s collections. When our scientists do fieldwork, they take tissue samples from the bird specimens they collect, like pieces of muscle or liver. Those tissue samples are stored at the Field Museum, frozen in liquid nitrogen, to preserve the DNA.”

Subsequently, in the Field’s Pritzker DNA Laboratory, the team embarked on the intricate process of sequencing the full genomes for each species, thereby deciphering the complete genetic makeup of each bird. Utilizing specialized software, they meticulously compared the billions of base pairs constituting these genomes to identify genetic commonalities among the diving kingfishers.

Remarkably, they uncovered several genetic adaptations in the fish-eating kingfishers, particularly in genes related to diet and brain structure. Notably, they identified mutations in the AGT gene, previously linked to dietary adaptability in other species, and the MAPT gene, which is responsible for encoding tau proteins and has connections to feeding behaviors.

Tau proteins play a crucial role in maintaining the integrity of small structures within the brain, but an excessive accumulation of these proteins can lead to negative consequences. In humans, conditions such as traumatic brain injuries and Alzheimer’s disease have been linked to an increased presence of tau proteins.

Shannon Hackett, drawing from her experience as a concussion manager for her son’s hockey team, expresses her curiosity about the resilience of kingfishers’ brains, pondering how these birds manage to protect their brains despite repeatedly diving headfirst into water.

“I learned a lot about tau protein when I was the concussion manager of my son’s hockey team. I started to wonder, why don’t kingfishers die because their brains turn to mush? There’s gotta be something they’re doing that protects them from the negative influences of repeatedly landing on their heads on the water’s surface.”

Hackett adds that tau proteins may be something of a double-edged sword.

The same genes that keep your neurons in your brain in all nice and ordered are the things that fail when you get repeated concussions if you’re a football player or if you get Alzheimer’s. My guess is there’s some sort of strong selective pressure on those proteins to protect the birds’ brains in some way.”

With the genomic variations now identified, Hackett is eager to delve deeper, aiming to understand the functional implications of the mutations found in the kingfishers’ genes and how they might alter the proteins produced. She is particularly interested in uncovering how these birds’ brains adapt to the impact of their diving behavior.

Chad Eliason adds, “Now, we know which of the underlying genes are shifting that help create the differences that we see across the kingfisher family. But now that we know which genes to look at, it created more mysteries. That’s how science works.”

Beyond shedding light on the genetics of kingfishers and potentially offering insights into brain injury research, Hackett emphasizes the invaluable contribution of museum collections to this study.

“One of the specimens we got DNA from in this study is thirty years old. At the time it was collected, we couldn’t do anywhere near the kind of analyses we can do today– we couldn’t even do some of this stuff five years ago,” adds Hackett. “It traces back to the ability of individual specimens to tell new stories through time. And who knows what we’ll be able to learn from these specimens in the future? That’s why I love museum collections.”

Source:

Image Credit: iStock