New gravitational wave data shows that when two black holes come together, they can give each other a kick and push each other out of their home galaxy.

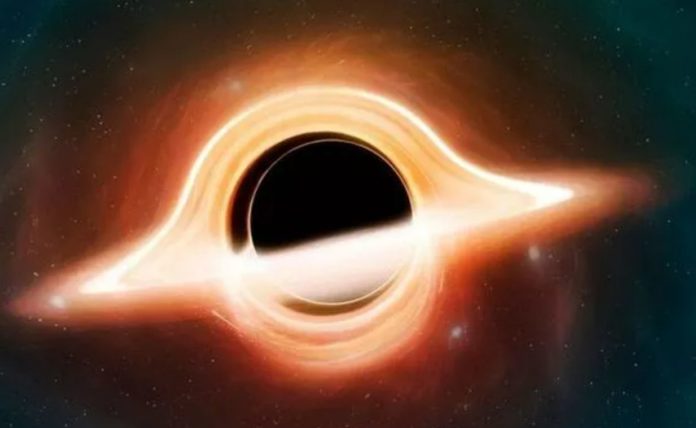

As the fundamental definition goes, black holes are regions of spacetime that have been warped by concentrated mass to the point where nothing — not even light — can escape their gravity beyond their “event horizon.” We can find them in a variety of methods, such as observing the high-energy radiation emitted by matter as it swirls into the holes or observing how their gravity affects the movement of adjacent things. Physicists can also use interferometers like Virgo in Italy and LIGO in the United States to detect gravitational waves released as black holes combine, bending the fabric of spacetime.

Some of the black holes physicists have observed in the cosmos appear to be “speeding,” moving much quicker than theoretical calculations would suggest.

Scientists speculated that the energy gained by these fast-moving black holes came from past merger events.

According to the theory, black holes that have merged can get a boost if most of the gravitational waves released by the collision go in one direction. This can happen if the two black holes that came together had very different masses or spins.

The merged black hole recoils in the opposite direction to conserve momentum. Physicists had no data to back up this notion until today.

When the merger’s orbital plane undergoes precession — a shift in the direction of a rotational axis — significant kicks are expected, which should leave a noticeable amplitude modulation in the gravitational wave signal.

In their study, Dr. Vijay Varma and his colleagues from the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics in Potsdam, Germany, looked at an event called “GW200129,” which is a merger of two black holes.

This is the first observation of a black hole merger with a clear and unmistakable precession signature in its gravitational wave output.

The signals of GW200129 detected by the LIGO–Virgo detectors were compared to predictions based on numerical relativity models.

The black hole created by the merging event, which has a mass 60 times that of the Sun, was given a kick of roughly 3,355,404mph, according to the researchers.

This is much faster than most galaxies’ escape velocity, and approximately three times faster than our own Milky Way.

The collision would have likely sent the final black hole hurtling out of its home galaxy, according to the study.

“Given the kick velocity, we estimate that there is at most a 0.48 percent probability that the remnant black hole of GW200129 would be retained by globular, nuclear star clusters,” Dr Varma added.

The discoveries could have ramifications for the existence of “heavy black holes,” which arise as a result of many black hole mergers.

Mergers that end in kicks, on the other hand, cannot be too common for heavy black holes to emerge.

If they happen too frequently, the resulting combined black holes will scatter throughout the wide intergalactic space, making future encounters extremely unlikely.

Future research, according to the team, will aid physicists in better constraining the rate of so-called second generation mergers, which can aid in the formation of larger black holes.

Professor Saul Teukolsky, a theoretical astrophysicist at Cornell University, is the leader of the Simulating eXtreme Spacetimes (SXS) Collaboration, under whose auspices the current investigation was carried out.

“This research shows how gravitational-wave signals can be used to learn about astrophysical phenomena in an unexpected way,” said Prof. Teukolsky.

“It had been believed that we would have to wait more than a decade for detectors sensitive enough to do this kind of work, but this research shows we can in fact do it now — very exciting!”

The study’s findings were published in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Image Credit: Getty

You were reading: Black Holes: Until Now, Physicists Had No Evidence To Support This Theory