A tribe of hunter-gatherers buried an infant girl in an Italian cave ten thousand years ago, right after the last Ice Age. They buried her with a plethora of their treasured beads and ornaments, as well as an eagle-owl talon, expressing their sadness and demonstrating that even the youngest ladies were valued members of their community.

An international team of experts working in a cave in Liguria, Italy, discovered the earliest reported burial of a newborn girl in the European archaeological record.

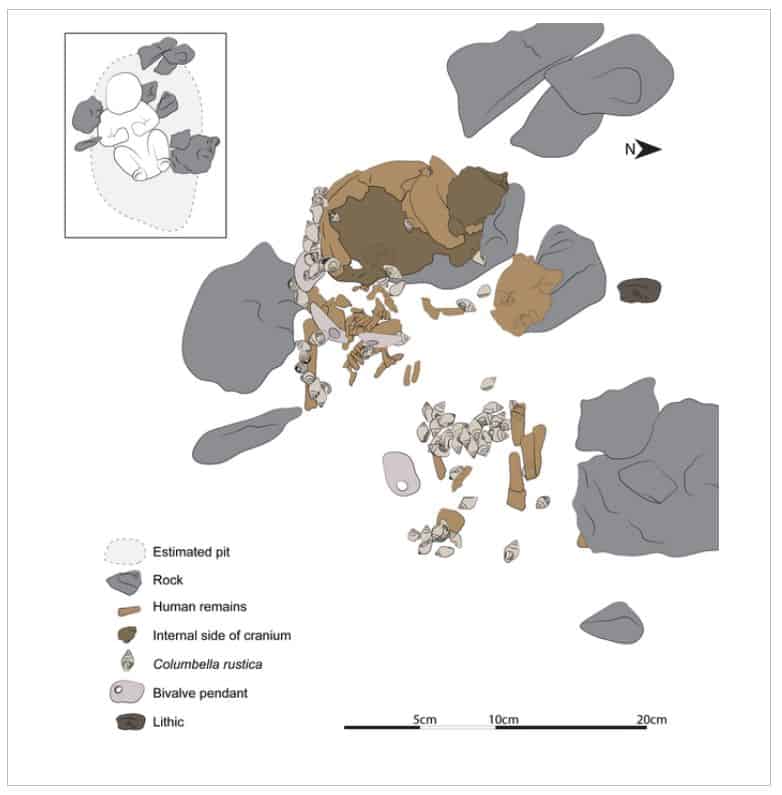

Along with the remains, the elaborately adorned 10,000-year-old burial included around 60 perforated shell beads, four pendants, and an eagle-owl talon.

The find sheds light on the early Mesolithic period, which is notable for its scarcity of recorded graves, and the seemingly egalitarian funerary treatment of a baby girl.

“The evolution and development of how early humans buried their dead as revealed in the archaeological record has enormous cultural significance,” said Jamie Hodgkins, PhD, paleoanthropologist and associate professor of anthropology at the University of Colorado Denver.

The burial was discovered in 2017 and the delicate remains were entirely unearthed in July 2018. Hodgkins worked at the University of Colorado School of Medicine alongside her husband Caley Orr, PhD, a paleoanthropologist and anatomist. Their codirectors on the project included Italian collaborators Fabio Negrino of the University of Genoa and Stefano Benazzi of the University of Bologna, as well as researchers from the University of Montreal, Washington University, the University of Ferrara, the University of Tubingen, and the Arizona State University Institute of Human Origins.

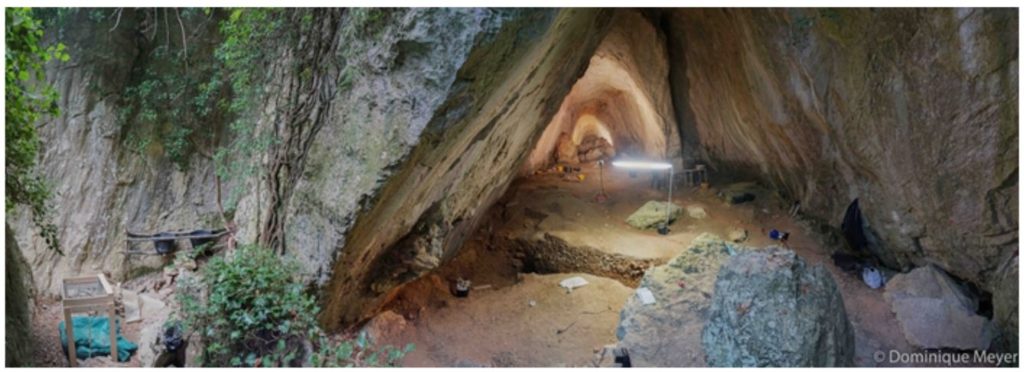

Arma Veirana, a cave in northern Italy’s Ligurian pre-Alps, is a popular destination for local families. Additionally, looters discovered the site, exposing the late Pleistocene tools that brought scholars to the area.

The crew spent the first two seasons of excavation near the cave’s mouth, discovering stratigraphic strata containing artifacts over 50,000 years old that are generally linked to European Neandertals (Mousterian tools). They also discovered remnants of old feasts, including cut-marked wild boar and elk bones and burnt fat. To gain a better understanding of the cave’s stratigraphy in relation to the artifacts, the researchers needed to reveal possible Upper Paleolithic deposits that could have provided the material for the more recently made stone tools discovered eroding down the cave floor.

As the team explored deeper into the cave, they discovered pierced shell beads. Hodgkins was sorting the beads in the lab when he realized the team was onto something. A few days later, the researchers exposed portions of a cranial vault and articulated lines of pierced shell beads using dental tools and a small paintbrush.

The researchers discovered significant information about the ancient burial through a series of examinations conducted with multiple institutions and numerous experts. Radiocarbon dating established that the child, dubbed “Neve,” existed 10,000 years ago, and amelogenin protein study and ancient DNA confirmed that the infant was a female from the U5b2b haplogroup of European women.

“There’s a decent record of human burials before around 14,000 years ago,” added Hodgkins.

“But the latest Upper Paleolithic period and earliest part of the Mesolithic are more poorly known when it comes to funerary practices. Infant burials are especially rare, so Neve adds important information to help fill this gap.”

“The Mesolithic is particularly interesting,” added Orr.

“It followed the end of the final Ice Age and represents the last period in Europe when hunting and gathering was the primary way of making a living. So it’s a really important time period for understanding human prehistory.”

The infant died 40–50 days after birth, and stress temporarily prevented the growth of her teeth 47 and 28 days before she was born, respectively. Carbon and nitrogen studies of the baby’s teeth proved that the mother had been feeding the infant a land-based diet.

An investigation of the ornaments adorning the infant revealed the level of care given to each piece and the fact that several of the decorations exhibited wear consistent with being passed down to the child by group members.

Along with the burial of a similarly aged female in Upward Sun River, Alaska, Hodgkins asserted that Neve’s funerary treatment demonstrates that the recognition of infant females as full persons has deep roots in a shared ancestral culture shared by peoples who migrated to Europe and those who migrated to North America. Alternatively, it may have evolved concurrently in people throughout the world.

Mortuary practices provide insight on historical societies’ worldviews and social structures. Child funerary care sheds light on who was considered a person and endowed with the traits of an individual self, moral agency, and group membership eligibility. Neve demonstrates that in her society, even the youngest females were considered as whole individuals.

And, because archaeology has generally been viewed through a male perspective, Hodgkins is concerned that we have missed out on many important stories.

“Right now, we have the oldest identified female infant burial in Europe,” Hodgkins added.

“I hope that quickly becomes untrue. Archaeological reports have tended to focus on male stories and roles, and in doing so have left many people out of the narrative. Protein and DNA analyses are allowing us to better understand the diversity of human personhood and status in the past. Without DNA analysis, this highly decorated infant burial could possibly have been assumed male.”

Archaeologists have generally presumed that figureheads and warriors were masculine in Western society. However, DNA tests have established the existence of female Viking warriors, nonbinary leaders, and powerful female monarchs during the Bronze Age. Discovering a grave like Neve’s is reason to examine archaeology’s past more closely, according to Hodgkins.

“This is about increasing our knowledge of women, but also acknowledging that we as archaeologists can’t understand the past through a singular lens. We need as diverse a perspective as possible because humans are complex.”

Source: 10.1038/s41598-021-02804-z

Image Credit: Jamie Hodkins, PhD, CU Denver / Claudine Gravel-Miguel

You were reading: 10,000-year-old infant girl burial uncovers a Mesolithic society that honored its most vulnerable members