A new and unwelcome phenomenon tied to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Targeted social media campaigns and frightening e-mails or texts and calls to scientists are not new: similar attacks have been made in the past on climate change, vaccines, and the impacts of gun violence. However, even scientists who were well-known before COVID-19 stated in a new study that abuse was a novel and unwanted phenomenon associated with the outbreak.

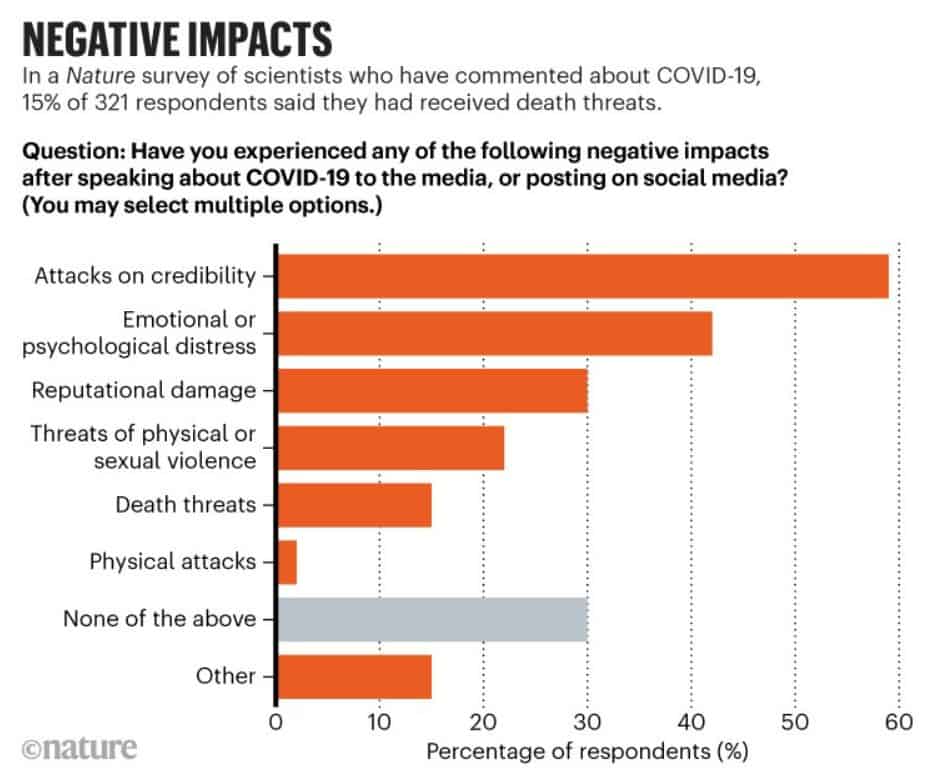

Nature conducted a survey of over 300 scientists who had given media interviews regarding COVID-19 — many of whom had also commented on the pandemic on social media — and reported widespread harassment and abuse; 15% reported receiving death threats (see the chart below).

Several well-publicized cases of harassment have been properly documented. Anthony Fauci, director of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, was appointed personal security officers after he and his family received death threats; Chris Whitty, the UK’s chief medical adviser, was grabbed and shoved in the street; and Christian Drosten, a German virologist, received a parcel containing a vial of liquid labelled ‘positive’ and a note instructing him to drink it. In one rare case, Belgian virologist Marc Van Ranst and his family were relocated to a safe home after a military sniper fled after leaving a note indicating his intention to attack virologists.

These are extreme cases. However, more than two-thirds of scientists in this study reported having negative experiences as a result of media interviews or social media comments, and 22% had received threats of physical or sexual harm. According to some scientists, their workplace had received complaints about them or their home address had been disclosed online. Six scientists claimed to have been physically assaulted.

Many wished for a more candid discussion of the scope of the situation.

“I believe national governments, funding agencies and scientific societies have not done enough to publicly defend scientists,” one researcher said in their survey response.

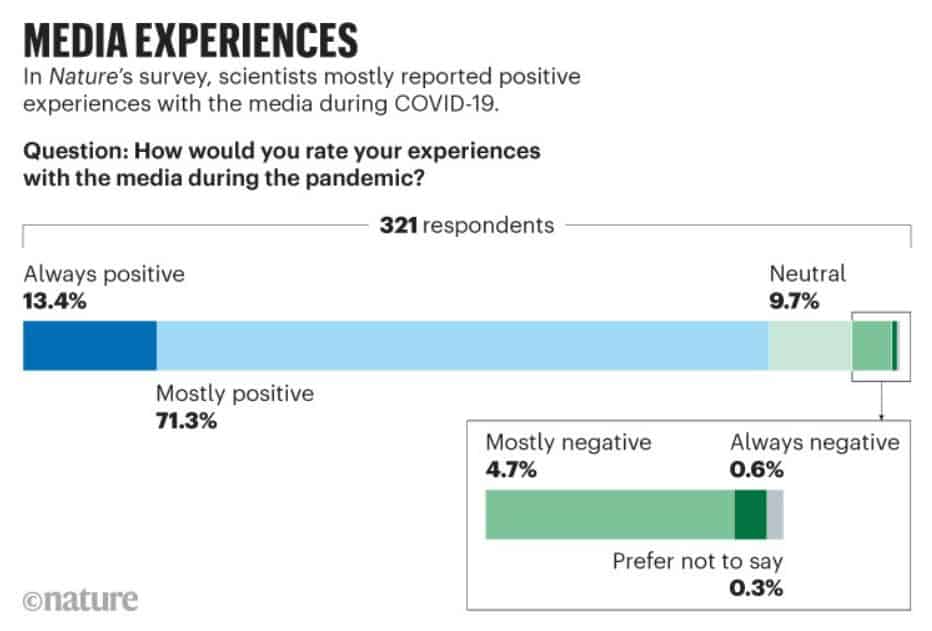

According to some academics, they have developed a tolerance for harassment, embracing it as an unwelcome but necessary side consequence of disseminating information to the public. And 85% of respondents indicated that their interactions with the media were always or mainly pleasant, even if they were afterwards harassed.

“I think scientists need training for how to engage with the media and also about what to expect from trolls — it’s just a part of digital communication,” one wrote.

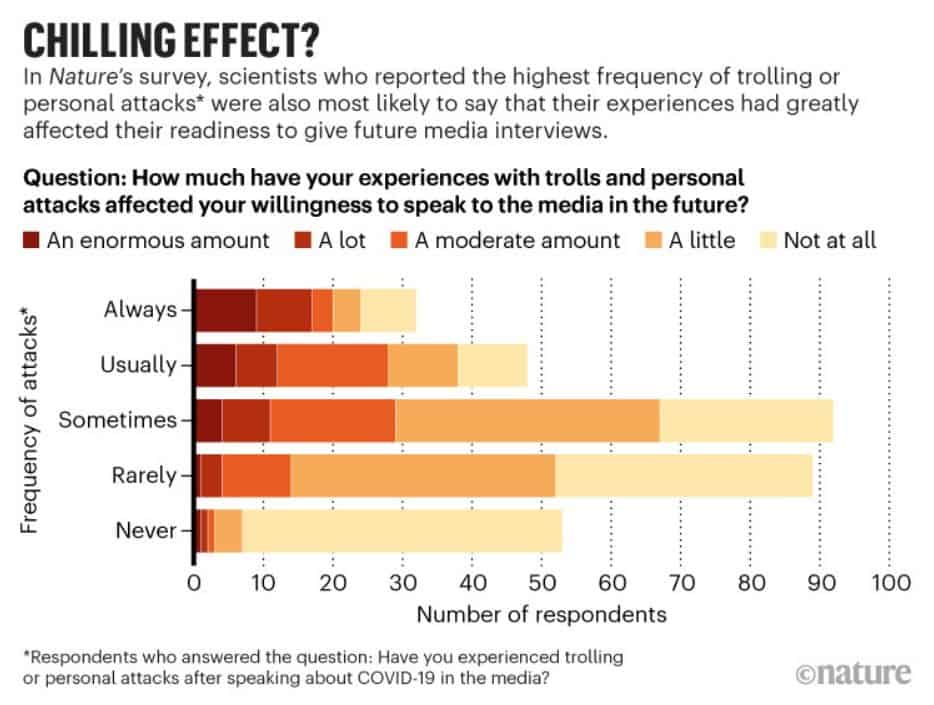

However, Nature’s poll indicates that, despite researchers’ efforts to shrug off harassment, it may have already had a serious impact on scientific journals. Scientists who reported higher rates of trolling or personal assaults were also more likely to believe that their experiences had had a significant impact on their future willingness to interact with the media.

This is alarming during a dangerous disease accompanied by a barrage of disinformation and misinformation, according to Fiona Fox, chief executive of the UK Science Media Centre (SMC) in London, an institution that compiles scientific comments and hosts press briefings for journalists.

“It’s a great loss if a scientist who was engaging with the media, sharing their expertise, is taken out of a public debate at a time when we’ve never needed them so badly,” she says.

The study adopted the Australian SMC’s poll and circulated it to scientists on their COVID-19 media lists in the United Kingdom, Canada, Taiwan, New Zealand, and Germany. Nature also emailed prominently quoted researchers in the United States and Brazil.

The findings do not represent a random sample of researchers who gave media interviews about COVID-19; rather, they reflect the experiences of the 321 scientists who chose to reply (predominantly in the United Kingdom, Germany and the United States). However, the statistics indicate that researchers in a number of nations are subjected to pandemic-related abuse, and the proportions reported were higher than in the Australian study. More than a quarter of respondents to the Nature survey stated that they have always or frequently received comments from trolls or have been personally assaulted as a result of speaking about COVID-19 in the media. Additionally, more than 40% stated that they had emotional or psychological discomfort as a result of their media or social media remarks.

To some degree, this mistreatment of scientists is a reflection of their increased public profile. And such criticisms may have less to do with the science than with who is speaking.

Both the Australian SMC and Nature’s survey, however, discovered no discernible difference in the percentage of men and women who receive violent threats.

Certain elements of COVID-19 science have been so controversial that it’s difficult to bring them up without eliciting a barrage of hate. Gideon Meyerowitz-Katz, an epidemiologist at the University of Wollongong in Australia who has accumulated a following on Twitter for his detailed dissections of research papers, says two major triggers are vaccines and the anti-parasite drug ivermectin, which was controversially promoted as a possible COVID-19 treatment without evidence of efficacy.

“Any time you write about vaccines — anyone in the vaccine world can tell you the same story — you get vague death threats, or even sometimes more specific death threats and endless hatred,” he says.

However, he was taken aback by the fervent defence of ivermectin.

“I think I’ve received more death threats due to ivermectin, in fact, than anything I’ve done before,” he says.

“It’s anonymous people e-mailing me from weird accounts saying ‘I hope you die’ or ‘if you were near me I would shoot you’.”

Andrew Hill, a pharmacologist at the University of Liverpool’s Institute of Translational Medicine, faced furious abuse following the publication of a meta-analysis in July by himself and his colleagues. It indicated that ivermectin was beneficial, however Hill and his co-authors later retracted and revised the study because one of the major studies they included was dropped due to ethical issues about its data. Following that, Hill faced an onslaught of images of hanged people and coffins, with attackers claiming he would face ‘Nuremberg tribunals’ and that he and his children would ‘fire in hell’. Since then, he has deactivated his Twitter account.

Natalia Pasternak, a microbiologist turned science communicator in Brazil, also noticed an increase in online attacks against her after she spoke out against the Brazilian government’s unproven COVID-19 treatments, which include ivermectin, the antimalarial drug hydroxychloroquine, and the antibiotic azithromycin. Pasternak established the Instituto Questo de Ciência — the Science Question Institute — in 2018 with the goal of increasing the use of scientific evidence in governance and public dialogue. When COVID-19 struck, Brazil “became the first country in the world to actually promote pseudoscience as a public policy, because we promote the use of unproven medications for COVID-19,” Pasternak said.

She has been on numerous media networks and created her own YouTube show, the Plague Diary. Commenters questioned her voice and looks, claiming she was not a genuine scientist. However, Pasternak asserts that the attacks rarely called into question what she was saying.

Additionally, some attackers have attempted to silence their targets through the use of the law. A group of Bolsonaro supporters attempted to sue Pasternak for defamation after she compared Bolsonaro to a plague on her YouTube show; the claim was dismissed. Additionally, Van Ranst has been sued for slander by a Dutch activist who is opposed to vaccination and public-health measures such as lockdowns in Belgium and the Netherlands.

Another subject that generates a great deal of hate is the origins of SARS-CoV-2. Both the Australian and UK SMCs report having difficulty locating scientists prepared to speak publicly about the subject out of fear of being assaulted. Fox reports that the UK SMC asked around 20 scientists about participating in a briefing on this subject, but they all declined.

Danielle Anderson, a virologist now at the University of Melbourne’s Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, received sustained, coordinated online and email abuse in early 2020 for writing a fact-checking critique of an article suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 may have leaked from China’s Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV). She was based at the Duke–National University of Singapore Medical School in Singapore at the time, but had partnered with the WIV since the 2002–04 SARS pandemic.

“Eat a bat and die, bitch,” one e-mail read.

Peter Daszak, head of EcoHealth Alliance in New York City, another researcher with a long history of WIV collaboration, has also faced abuse. Daszak, who travelled to Wuhan in January as part of a WHO-coordinated investigation into the origins of SARS-CoV-2, claims he received a letter containing white powder, his address was released online, and he receives regular death threats.

When it comes to the origins of SARS-CoV-2, harassment has cut both ways. Alina Chan, a postdoctoral researcher at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard in Cambridge, Massachusetts, has come under fire for her research into the possibility that the pandemic was caused by virus exposure in a laboratory or research site (often referred to as the ‘lab leak’ hypothesis). Finally, she asserts, abusive attacks are detrimental to the perpetrators.

“They make the people on their own side appear unreasonable and dangerous,” she says.

“Second, they make it difficult to hold people accountable because now everyone is distracted by having to address the excessively abusive attacks.”

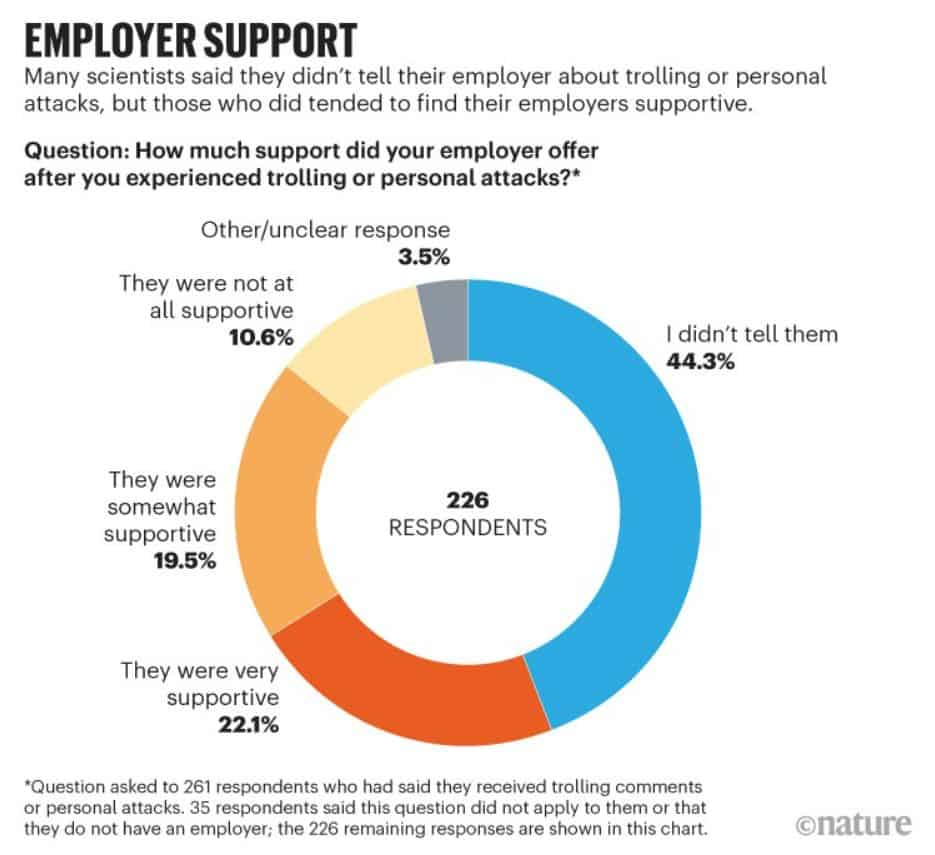

The survey also revealed that 44% of scientists who reported being trolled or experiencing personal attacks never informed their employer. However, nearly 80% of those who did regarded their company to be ‘very’ or ‘somewhat’ supportive.

For scientists who receive online abuse, individual coping strategies include trying to ignore it; filtering and blocking e-mails and social-media trolls; or, for abuse on specific social-media platforms, deleting their accounts. But it’s not easy.

When Infectious-diseases physician Krutika Kuppalli informed her university, for example, she was given a considerably closer parking place and the university’s IT department tried to ban some of the university’s regular abusive e-mailers.

Tara Kirk Sell, a public-health researcher at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore, has faced online and e-mail abuse, most recently following an appearance on a US conservative television network to discuss COVID-19. One e-mail advocated for the execution of Sell and her colleagues.

Sell, a former professional athlete who had encountered harassment submitted the e-mail to officials, who forwarded it to school security authorities. They conducted an investigation, identified the sender, contacted them, and advised them to cease sending. Sell received no further communication from them.

“I think that a lot of people don’t realize that they should report their harassment to their institution,” she says.

One Australian epidemiologist — who requested anonymity to avoid further harassment — told Nature that she was forced to seek assistance from her institution after receiving “vile, sexualizing” e-mails in response to her media interviews on COVID-19. Initially, her institution implied that she was responsible for dealing with it. They took action only when she compared the online abuse to someone rising up in her lecture theatre and shouting the same comments, which included an insulting reference to her sexual anatomy.

“You would march that person off the campus,” she said.

Her institution eventually removed her contact information off its website and connected her with a campus security officer.

The Royal Society of Canada established a working committee on ‘safeguarding public advice’ in May in response to an uptick in attacks on scientists and public-health authorities. Before the end of the year, it plans to produce a policy briefing.

“Our fundamental concern is what do we do to make sure that expertise can still reach the public and it’s not silenced by this kind of activity,” said working-group chair Julia Wright, an English literature scholar at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Canada, and president of the Royal Society of Canada’s Academy of the Arts and Humanities.

According to Wright, several colleges have official protocols in place to address attacks on faculty, which range from ensuring that individuals have access to counselling and security services to publicly expressing support for their academics and academic freedom. These statements are frequently really beneficial, Wright notes, but they can also breathe new life into an otherwise dormant harassment campaign.

“This is something that I think we’re all still trying to figure out strategies for dealing with.”

Much abuse occurs on social media, posing the perennial question of whether social media corporations take responsibility for what is posted on their platforms. 63% of scientists who replied to Nature’s study said they used Twitter to comment on COVID-19-related issues, and around one-third said they were ‘always’ or ‘usually’ attacked on the network.

According to some scientists, they have learned to tone their remarks about COVID-19. Robert Booy, an infectious-diseases paediatrician at the University of Sydney, says he learned lessons from his hasty remarks during a hurried telephone interview done on the side of the road.

“I said, ‘you can have a vaccine, or you can go to heaven early’,” he recalls.

“I should not have been rushed, I should not have been glib and I should have been on home ground and calm,” he says.

While some scientists have endured harassment, others have refrained from commenting on even relatively uncontroversial subjects. Nature’s study discovered examples of scientists remaining silent: a few anonymous respondents stated that they were scared to speak about some topics due to witnessing others being abused.

Anderson believes her experience has altered her approach to science communication, and she now declines the majority of media interviews.

Souce: Nature doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-02741-x

Image Credit: Getty

You were reading: How COVID-19 damaged science — some of the harm could be permanent